Informational series on how America can maximize benefits of IRA investments through 2036

Well, it depends on how it’s made. Like, a lot.

This reality underlies 2 years of vociferous battle over federal hydrogen incentives. The front line of that battle is over a specialized energy accounting tool called a REC.

This topic I know well. As co-chair of the task force that developed the implementation framework for the Texas Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), I was heavily involved with creation of the Texas Renewable Energy Credit (REC) program and among the earliest champions for their use toward voluntary environmental claims. In 2001, Texas created the national template for tradable RECs with its first-in-the-nation REC trading program implementing the Texas RPS requiring 2,000 MW of new renewable energy capacity to be deployed in the state. While a valuable “starting point”, RECs simply validate renewable energy deployment but do not characterize emission displacement. This is a critically important distinction, because 45V is about emission reductions (kilograms of CO2), not about deployment of renewable resources (Megawatt-hours).

What a REC offsets (for accounting purposes) and what it displaces (in reality) can be two entirely different things. A Renewable Energy Credit (REC) can offset something that’s a little bit dirty or a lot dirty, with the offset emissions all getting pushed into the accounting system’s “residual mix”.

This means that a widget of clean generation represented by a REC is not necessarily taking emissions out of the atmosphere. This is a known weakness with using “book and claim” accounting to meet carbon intensity requirements for clean hydrogen. Fortunately, by requiring strict three pillars accounting, uncertainty will be low because the emissions accounting ledger must balance every hour.

Why is accurate accounting so important? Two reasons:

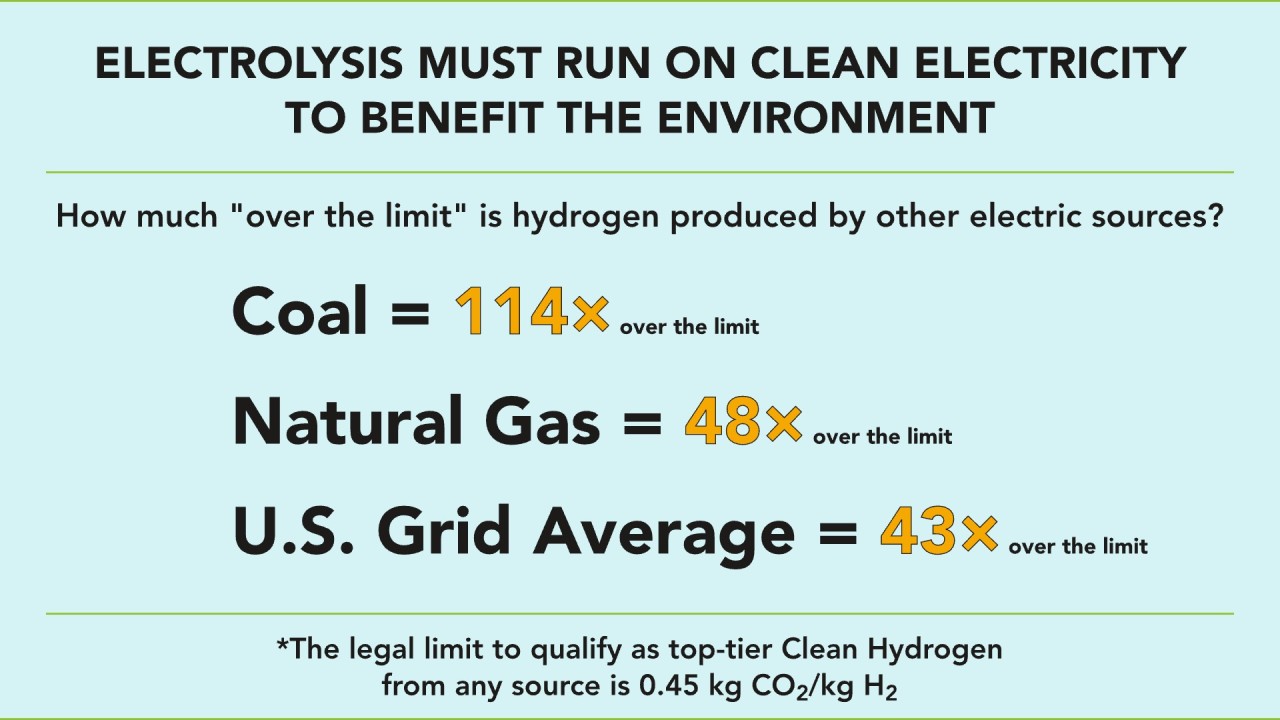

1. The law requires it. Incentives for hydrogen are defined in the IRA statute in increasing tiers based on carbon intensity of the hydrogen production pathway. The maximum emissions allowed by law to receive the highest level of 45V Production Tax Credit incentive ($3 per kg of H2) is explicitly stated as less than 0.45 kg CO2e per kg H2.

2. Loose accounting is a gateway to known problems. Using a fossil fuel (coal, petroleum or natural gas) to make electricity that is turned back into a fuel (hydrogen) is a very inefficient and tremendously polluting process.

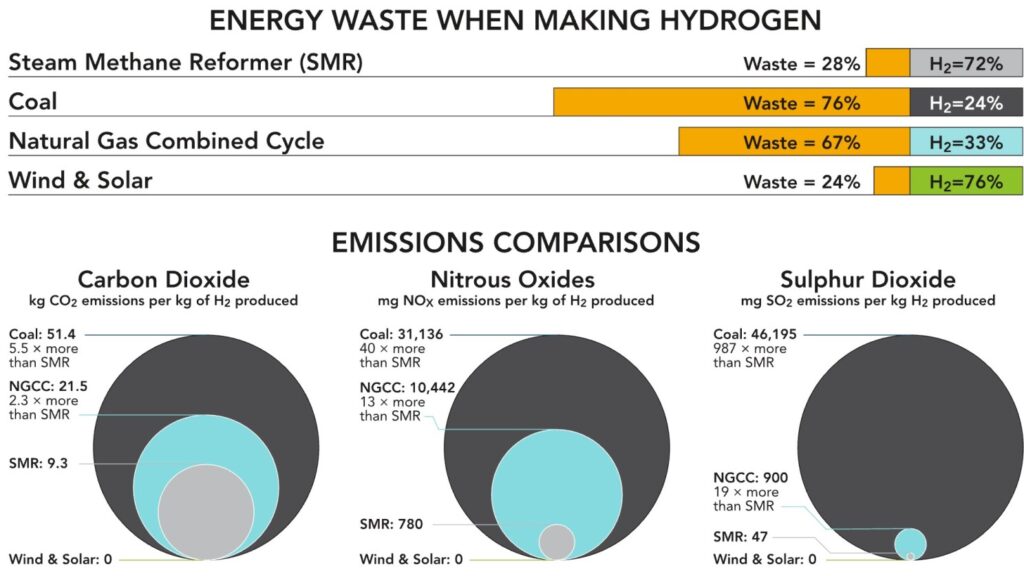

Some have argued that electrolyzers are just big new electric loads and should not be treated differently than Electric Vehicles. But unlike EVs, which are highly efficient, electrolysis is not. For the status quo method of making hydrogen today in a Steam Methane Reformer (SMR) using natural gas without carbon sequestration (so-called “grey” hydrogen) about 72 percent of the natural gas BTUs that go into the SMR pop out the other side as hydrogen. Even when using the most efficient natural gas combined cycle technology to make electricity, only about 33 percent of the natural gas BTUs that go into the power plant and through an electrolyzer will ultimately come out as hydrogen. And in the process of having to use two-and-a-half times as much natural gas fuel, it will produce twice the CO2 and emit 13 times the smog-forming NOx as a grey SMR.

Making electrolytic hydrogen by burning coal is vastly worse than status quo hydrogen production: five times higher carbon emissions, 40 times the NOx, and 1,000 times the SO2 emissions. Quite simply, it’s a terrible idea for the environment to use coal or natural gas to make electrolytic hydrogen. An even worse idea is to subsidize it. For electrolysis to be a net benefit, it must be very clean and very low-cost.

However, electrolyzers are currently expensive and their owners understandably want to operate them as much as possible to recover their investment. Yet renewable energy sources vary with the cycles of nature. When clean electricity is not available, electrolyzer owners either need to ramp down production, invest in creative solutions like diversified clean electric supplies and batteries, or lobby like hell to get regulators to look the other way.

This is where the annual matching debates intensifies, leading to a battle of the studies. On one side, experts vehemently cautioning against the massive increase in emissions that will follow loose rules, on the other, respected institutions offering studies claiming that hourly matching provides little benefit, or even that annual matching (loose accounting) will result in less emissions than hourly matching (strict accounting).

That fascinating finding (that loose accounting is better than strict accounting) begs explanation (and careful scrutiny of simplifying assumptions). Why would making hydrogen on a windless night using smokestack technologies lower emissions compared to not running at all? The fact is, when electrolyzers run off electricity from the grid, coal, or natural gas, CO2 emissions are between 40 and 120 times higher than the legal limit to receive top-level 45V incentives.

This degree of non-compliance can blow up the integrity of carbon intensity accounting for the entire year even with only a tiny fraction of coal or gas driven electrolysis blended into clean hydrogen. Under annual matching, electrolyzer operation and clean supply are fully decoupled. This creates a very high uncertainty in tracking actual carbon intensity. In springtime, an abundance of renewable energy production often exceeds transmission capacity (California’s “duck curve” is a classic example). This results in a lot of RECs produced in the spring, but also high levels of curtailment. Substantial amounts of Springtime RECs are produced by cannibalizing other renewable energy generation (resulting in zero actual emission reductions for some RECs). Under annual matching, those spring RECs could be used in summer to enable higher levels of electrolyzer operation, often at night during the ozone season, by running gas and/or coal plants with massively higher emission levels than the SMRs they are incentivized to replace.

Annual Matching (of RECs) is a poor tool for claiming carbon intensity. The Annual Matching loophole allows annual RECs to claim the label of “clean”, even though what they’re often doing is blending in dirty hydrogen with clean hydrogen to increase output volume and get more incentives.

The 45V debate that resolves how clean “Clean” Hydrogen actually is may ultimately boil down to this: to what extent are federal regulators willing to look the other way?

As the father of two teenagers, the following analogy comes to mind. If a teen receives an allowance based solely on keeping their room clean, which would you expect to result in the room staying cleaner: proving it once per year? Or once per hour?

Details for the analysis described in this article are available at this link.